The Formula of Concord – Commentary

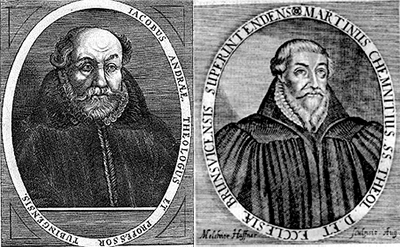

Jacob Andrae and Martin Chemnitz, the two principal authors of the Formula of Concord.

The last of the Lutheran Confessions, the Formula of Concord, is different from the former confessions in that it has a different focus. The concern is not primarily with Roman Catholic or Reformed theology, but fellow Lutherans confessing together. For that reason alone it is a significant confession for the Lutheran Church today.

The genius of the Formula of Concord is that it shows us how to do theology today. First, it teaches us to define the disputed issues. Then it seeks to find clarity on the controversy by looking at the Scriptures, the early church and the former confessional writings. On that basis it makes a clear confession. “We believe, teach and confess…” “We reject and condemn…”

This latter aspect of the Formula sometimes makes us uneasy. We aren’t too sure about rejecting and condemning, even when we’re talking about theological positions and not individual people. It doesn’t sound loving. We aren’t comfortable drawing boundaries.

However, the Formula does not draw boundaries to stifle the Gospel. It draws boundaries to safeguard the Gospel so that people with troubled consciences will continue to hear its comfort and be warned of the errors that will lead them back under the law. The Formula has the Gospel at its heart and is a very pastoral document.

In 1537, in his preface to the Smalcald Articles, Luther spoke of his concern that some who claimed to be Lutheran twisted his writings to support their viewpoint. He said it didn’t really matter while he was alive because he could teach, preach and correct where necessary. But in a prophetic utterance he said, “Imagine what will happen after I am dead.”

This period of history is well summarized by William Moorhead: “After Luther’s death (1546) and the Smalcald War (1547), the Lutherans in the Holy Roman Empire were in a precarious position. Without their leader, the pastors and churches faced opposition from the outside and dissension within. Although the Lutherans achieved appropriate legal status in the Holy Roman Empire through the agreement known as the Peace of Augsburg in 1555 (they could confess and practice their faith freely), they soon were divided over significant doctrinal issues. It was clear that concord was necessary if the Evangelical church was to survive.” (W. Moorhead, The Formula of Concord Study Guide, 1999).

The two main workers for unity and chief authors of the Formula of Concord were Jacob Andreae and Martin Chemnitz. Andraea first wrote Six Christian Sermons in 1573 which Chemnitz, with the help of others, later reworked into the Swabian-Saxon Concord. A revised document was developed at Torgau in 1576 and a summary written soon after. These two documents, the Epitome (the smaller summary) and the Solid Declaration (the comprehensive confession) were accepted in 1577 as the complete Formula of Concord.

While the history is interesting, the Formula’s content is more significant. It contains twelve articles and I encourage you study the Formula. You can use secondary resources like One in the Gospel (Dr.F.Hebart), or the study guide written by William Moorhead referred to above. However it is best to read the Formula itself and especially the Scripture references forming the foundation for what it teaches.

Topics covered are original sin, free will, justification, good works, law and gospel, the third function of the law, the Lord’s Supper, the person of Christ, Christ’s descent to hell, liturgy and adiaphora, election and foreknowledge, and religious factions and sects.

Why study the Formula? It will help you work with a Lutheran approach to mission and conversion (Article 2); to find the right place for good works in Christian living (Article 4); to find the comfort in being one of God’s elect (Article 11); to find the comfort of the Gospel (Articles 3,7,8,11); and to base decision making in liturgical matters on what God has commanded and instituted (Article 10).

Since the early Lutherans had more than their fair share of disputes, they left us a great confessional legacy. We have twelve articles on issues still relevant and alive in our own churches. We also have a way of proceeding when we face significant conflict:

- work out what the problem actually is

- discover from Scripture and the early church what was taught and what was in error

- reflect again on your current controversy

- make your own good confession both to what is taught and confessed and what is rejected for the sake of keeping the comfort of the gospel.

Dr. Andrew Pfeiffer

Lutheran Church of Australia

(Originally published by the International Lutheran Council in 2005)

You can read an older translation of the Formula of Concord online here for free. For an up to date translation that’s easy to read, check out The Book of Concord – A Reader’s Edition from Concordia Publishing House.